Damn. I’m late. If there’s any trouble dropping Denny off at my sister’s—and there’s always trouble dropping Denny off at my sister’s—I might not make my first appointment, and Violet, the lady I do at the assisted living place all the way out in Shirleysburg won’t mind, her mind’s pretty much gone, and all she cares about is having pretty little twinkles on each finger, not when they get applied. But after Violet is a wedding clear over to Franklin County, and brides are the worst. The absolute worst.

Damn. I’m late. If there’s any trouble dropping Denny off at my sister’s—and there’s always trouble dropping Denny off at my sister’s—I might not make my first appointment, and Violet, the lady I do at the assisted living place all the way out in Shirleysburg won’t mind, her mind’s pretty much gone, and all she cares about is having pretty little twinkles on each finger, not when they get applied. But after Violet is a wedding clear over to Franklin County, and brides are the worst. The absolute worst.

Except for Denny when he doesn’t want to stay with my sister.

“Look what I have for you,” I tell Denny when he wanders into the kitchen, still in his pajamas—bottoms only, slippers on his feet, of course—with his old baby blanket wrapped around both shoulders like some superhero cape. “French toast.”

It’s really just toast-toast on a plate with syrup poured over it—eggs are pricey and I save the milk for Denny to drink—but Denny doesn’t know the difference.

He sits down and begins to eat.

I look at the clock. We have to get going earlier in the mornings but it’s hard. Denny is up in the night a lot—his sheets bother him, and he tosses and turns, rustling till all hours—and then I have trouble waking him up.

I stand by the counter, tapping my toe but not rushing Denny. It’s a cascade with him: do one part of the routine wrong, and the fuss he kicks up makes the next part go wrong too, and then the next, and the next…

He leans over, licks up the last swirl of syrup from his plate, then stands up.

I whisk the plate away, start to wipe the syrup off his nose, then stop like I touched an electrical outlet. I’d almost touched his nose, how stupid can I be?

“Can you go get dressed?” I ask Denny, hearing a quaver in my voice.

Denny doesn’t notice it.

I can’t believe it when he turns and leaves the room.

The trouble started when Denny turned two. Up till then he was an absolute angel, didn’t talk much and the pediatrician kept asking questions about that, but Denny didn’t give me one lick of trouble, and kids start talking at all different ages, the books I read said so.

Now he gets upset at my sister’s daycare when there are other kids around, which is always, and maybe that’s normal, socialization can be hard. But dumb stuff also bothers Denny. My sister likes the kids to take off their shoes in the house, and Denny can’t stand it, walks around as if the carpet is on fire and he can’t touch it with his feet. He’ll get down in a big lump on the floor, put his blanket over him—woe is me if we forget his blanket—and just howl.

Some days are better than others, and today Denny is having a good one. He appears in the kitchen, wearing pants, shoes, of course, but also a shirt, holding his blanket.

“Can we get in the car now?” I ask him. It’s stupid to have to ask a kid, but this works best with Denny.

He leaves the kitchen. I walk out after him, holding my breath.

I plan things out in my head as I drive to my sister’s. If I just do decals on Violet today—which she likes just as much—I can make it to the bride. Up here it’s not like in the city where everyone gets their nails done all the time. Up here my appointments are spread out, eighty miles apart sometimes, and I have to take every one I get, or forget milk and eggs, I won’t even have any bread for Denny.

Denny’s still being good as we walk across the lawn to my sister’s. I don’t hold his hand—he’s never let me do that—but he stays by my side. And it’s quiet inside the house, which is good. Denny gets worse when the other kids are crazy.

But all hell breaks loose when my sister makes one mistake.

“This stinks to high heaven, let me wash it for you,” she says to me. “Jane got muddy when we went outside, and I have to thrown in a load anyway.”

That’s why the kids are so quiet—they had a big adventure. I look at them all sitting in a ring around the computer, playing some game. Jane’s wearing a too big pair of overalls.

Denny’s holding onto his blanket. He doesn’t realize my sister has one corner in her hand.

When he does, when he feels the resistance, he begins to yodel.

That’s what it always sounds like to me when he gets upset. Big, spiraling yowls that climb higher and higher. It doesn’t do any good if I hold him, try and comfort him. In fact, it makes it worse.

I just clap my hands over my ears and wait for it to stop.

“I forgot, I forgot!” my sister cries, dropping the blanket like it sliced her.

Denny strips off his clothes. He clutches the blanket to his chest, dropping to the floor and rocking back and forth till he starts to calm down.

The other kids don’t even look up from their game.

My sister has walked off, and when she comes back, she’s holding a book in one hand.

“I got this for you. Read it when you can,” she says. “And go. He’ll be all right now. We’ll both be all right. I just forgot.”

I look down at Denny. He’s quiet, blanket wrapped around his small body.

He doesn’t answer when I say goodbye.

I do Violet’s nails faster than I ever have. She doesn’t mind, just looks at each one with its little sticker, and preens for the other ladies in the home, all staring blankly at the TV.

I need to hurry to make it to the bride.

***

You can tell a lot about people from their nails. Some days I feel like a psychic, but it’s really just reading their nails.

The bride’s are ragged and torn. That tells me all is not peachy in marriage land.

And no wonder. As I’m trying to file her tips, smooth them out a bit, and apply a nice coat of color, she’s telling me all about her honeymoon. She’s going into the woods with her husband, taking a canoe trip. Who’d want to go camping on their honeymoon?

But I’m trying to be nice about it, upbeat. It doesn’t do to upset brides—they’re like Denny. This one seems okay, though. She spots the book my sister gave me. It starts to slip out of my purse, and even with her nails still wet, she grabs it before it falls.

“Careful, your nails!” I scold her.

Her sister comes in, carrying the dress.

For a moment, I just stop and stare. Oh, to wear a dress like that. Imagine what Denny would do with that dress, so smooth and silky. It wouldn’t rub against his skin like that rough rug at my sister’s.

The bride is holding the book out, carefully, so her nails won’t smear, thank goodness, I don’t have time for any redo’s, and I see the cover.

A little boy sitting in a rocking chair, all alone.

Life on the Spectrum it’s called.

“Good luck,” the bride says softly as I slide the book out of her hand.

She’s going into the woods with some guy she’s clearly worried about marrying, and telling me good luck with a gentle smile on her face.

I was wrong about brides, this one anyway.

I really hope she makes it back out of the woods.

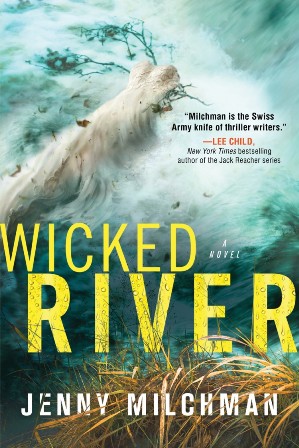

You can read more about the newlyweds mentioned in the above piece in Wicked River.

Six million acres of Adirondack forest separate Natalie and Doug Larson from civilization. For the newlyweds, an isolated backcountry honeymoon seems ideal-a chance to start their lives together with an adventure. But just as Natalie and Doug begin to explore the dark interiors of their own hearts, as well as the depths of their love for each other, it becomes clear that they are not alone in the woods.

Because six million acres makes it easy for the wicked to hide. And even easier for someone to go missing for good.

As they struggle with the worst the wilderness has to offer, a man watches them, wielding the forest like a weapon. He wants something from them more terrifying than death. And once they are near his domain, he will do everything in his power to make sure they never walk out again.

About the author

Jenny Milchman is the Mary Higgins Clark award-winning and USA Today bestselling author of four psychological thrillers, including her May release, Wicked River.

All comments are welcomed.

This sounds too dark for me, even if it sound good.

Gram, I appreciate your reading this piece! Wicked River *is* dark, you are right…but the thing about my books is that victory always happens in the end. I love writing stories where the good guys win. I don’t know if that will make a difference for you since there are definitely twisted moments before I get there. But it’s the triumph of justice I love in a book. Take care!